We just got back from the biennial High Energy Physics conference held by the European Physical Society, this year in "The North of England, at Manchester".

We just got back from the biennial High Energy Physics conference held by the European Physical Society, this year in "The North of England, at Manchester".

The poster for the conference was a nice Lowryesque image of the city, with matchstick physicists heading for the brand new Bridgewater Hall, where the main sessions were held.

As usual with conferences, the days were filled with rather intense schedules of parallel and plenary talks, while most evenings were kept aside for social events, where attendees discuss the day's talks with their colleagues and new people they have met, and which are usually accompanied by refreshments to help the discussions along (including the Beer Tasting that was organised by Lee Thompson of Sheffield, which I certainly appreciated).

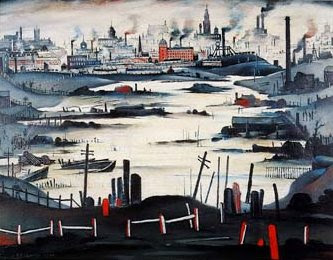

Most of these social events involved Dave Wark, our colleague on T2K at Imperial, in his role as the chair of High Energy Physics at the EPS, standing up and trying to tell jokes in a room seemingly chosen such that no one was able to hear him. The first of these was at the very impressive Manchester Town Hall, where it was clear to see (but not hear) that the Lord Mayor was enjoying Dave's speech very much indeed. I later learnt that he was rattling off the names of physicists from Manchester who had made Nobel Prize-winning contributions to our field. This list included the likes of Rutherford, Chadwick, Blackett, Bethe and several more, which is actually quite amazing. On the Sunday off, Dave and I checked out "The Lowry" gallery, where many of LS Lowry's works are on display, along with artefacts from life in the Industrial North, with contrasting images expressed mainly through paintings, photographs, Coronation Street (the TV soap for our international readership), and Labour Party pamphlets. It is a great day out and puts Manchester as we see it now in proper perspective. It was curious to note, however, that the conference poster was for some reason not based on Lowry's Manchester as depicted in paintings such as "The Lake".

On the Sunday off, Dave and I checked out "The Lowry" gallery, where many of LS Lowry's works are on display, along with artefacts from life in the Industrial North, with contrasting images expressed mainly through paintings, photographs, Coronation Street (the TV soap for our international readership), and Labour Party pamphlets. It is a great day out and puts Manchester as we see it now in proper perspective. It was curious to note, however, that the conference poster was for some reason not based on Lowry's Manchester as depicted in paintings such as "The Lake".

Coming out of "The Lowry", one is confronted by "The Lowry Outlet Mall". Perhaps celebrating Manchester's place as the centre of consumer culture in the North would have pleased the artist. Then again perhaps not.

One of the centrepieces of this conference is the presentation of the EPS Prizes. This year the main prize went to Makoto Kobayashi and Toshihide Maskawa, of "Kobayashi-Maskawa Theory" fame, and the K and M in the "CKM Matrix", the "C" being Nicola Cabibbo. Their paper in 1973 showed that symmetry violations that had been seen in nature, but difficult to incorporate into the understanding of physics at the time, could be described if 6 quarks existed, which were linked together through a 3 by 3 component matrix. This was at a time when the existence of quarks themselves, and whether there were 3 or 4, was a point of contention (though I would like to state that was quite a bit before my time!).

I'll leave it to our colleagues on BaBar and LHCb and DZero to remind the world of the significance of that particular Matrix....

Kobayashi was able to make it here and gave a presentation in acceptance of the prize. Although both K & M were at Kyoto University when they wrote their seminal paper, he clearly wanted to demonstrate that the work was a result of the Nagoya tradition of theoretical and experimental physics, just like the earlier MNS (Maki-Nakagawa-Sakata) matrix that we have been probing in our neutrino experiments.

Later in the week I bumped into one of my 4th year project supervisors at Kyoto, Prof Masaike, who I hadn't seen for, well, shall we just say a very very long time. He is close to Prof Maskawa (whose Quantum Field Theory course I remember sitting in), and over a pint of some nice dark Mild, he let me know that not only was Maskawa unable to make it to this particular conference, but he has actually never left the country ever in his life. Perhaps it will take even more than the EPS prize to persuade him to travel outside of Japan....

29 July 2007

A Week in the North of England

Post by Yoshi

Posted on

Sunday, July 29, 2007

1 comments (Read/Add)

![]()

Labels: EPS HEP Conference, Kobayashi Maskawa, Manchester

14 July 2007

What you missed at the Staff Party

Post by Patrick Wednesday all Imperial Staff were invited to the Centenary Staff Party, basically a big garden party on Queen's and Prince's Lawns. If you didn't attend, here's what you missed:

Wednesday all Imperial Staff were invited to the Centenary Staff Party, basically a big garden party on Queen's and Prince's Lawns. If you didn't attend, here's what you missed:

- All shop and restaurant staff dressed in Edwardian style.

- A chance to see the inside of the giant marquee on Queen's lawn. Rumors that it's the largest marquee in the world are definitively wrong. It's not even the largest in the borough, as some websites claim the world's largest marquee was used at the Chelsea Garden show.

- The Fab Beatles, a Beatles cover band specialised in the early years up to and including Help! but without Yesterday. I learned that to make a good Beatles cover band you need four guys including one left-handed, one who can play the guitar, one who hardly can play drums and one wearing glasses, all of them with the appropriate hairdo. The latter John-guy didn't follow the rule and had anachronistic long hair. But he was clearly the best approximation among the four.

- Fake That, another tribute band. Honestly, I couldn't really judge how good they are as I don't really know what they are supposed to be faking... Ask Yoshi, he seemed to be much more knowledgeable. There's a picture of the band above, but my autofocus seemed more interested by the balloon in front of the stage.

- And of course, the rector's dance. Luckily youtube saved it for the posterity.

Overall it was a nice party. College should make it annual! I don't want to wait 100 years for the next one!

Posted on

Saturday, July 14, 2007

1 comments (Read/Add)

![]()

Labels: beatles, imperial centenary party, rector's dance, take that

13 July 2007

Royal Visit

Post by Morgan

I had a unique experience for an American this week: seeing the Queen in person. She visited the College as part of the Centenary events, and had a quite a busy day from what I've read---but I guess that's always the case when she visits someplace. In the picture I've posted, she is walking through Upper Dalby Court here in the South Ken campus with the Rector, Sir Richard Sykes, having just dedicated the new Biomedical Engineering Institute and on her way to congratulate the College on 100 years of greatness. I was one of the "well wishers" who gathered to greet her en route. I'll confess that it was fun because I have always been a fan of pomp and circumstance, but I was disappointed that she didn't have time to chat because I had honed my elevator pitch about experimental particle physics and was quite prepared to make her love our field. Another time, perhaps.

Posted on

Friday, July 13, 2007

0

comments (Read/Add)

![]()

27 June 2007

To What End?

Post by OnuoraOf the long list of questions that I find interesting to mull over every now and again, I guess one of the more important ones would be my desire to understand the role of HEP in contributing to the well-being of society. Think about it; of what use is HEP to the day-to-day dynamics of society. When I leave the office and am out with my friends how does HEP contribute to my life? If I'm out shopping, sightseeing maybe, how does HEP contribute? Or if I'm simply spending time with family how does HEP contribute to how I interact with them? Another way to look at it would be to ask: how does HEP contribute to my understanding of myself as an independent entity with a role in society?

These questions are not asking about the opportunities that arise from working in a HEP environment such as travelling, attending conferences and the like. They are asking about the intrinsic purpose of HEP with respect to humanity's existence in the sea of creation. To answer, perhaps a good starting point would be to take a step back and try to figure out why HEP and indeed all institutions of knowledge became necessary in the first place.

The first important clue is that every human endeavour, be it Science, Technology, The Arts, Economics or Religion has as its original goal the desire to study and understand the human being, the environment or the interaction between the two, where the environment in this case refers to all physical creation that is separate from the human being, i.e. the earth, the universe, and so on.

The second clue is that a system, any natural system, will be composed of elements that are each unique. The uniqueness of each element automatically generates the property of diversity within the system. In a system that is composed of sentient, self-aware elements, for example human beings, this leads to the phenomena of demand under which each element recognizes its deficiencies relative to the strengths of the other elements within the system and reacts to this by striving to address the balance.

The third clue is that the act of striving is a natural action that is induced and controlled by the principle of evolution that permeates all creation.

And so combining clues 1, 2 and 3, we are left with the conclusion that HEP and indeed any other human endeavour exists for no other reason than to serve the phenomena of demand which is itself a natural attribute that is inherent within any system in creation. This is a sweeping statement. And it is one that raises a lot questions foremost of which are: What is demand? What is evolution? How are they defined and what are their origins? The answers to these questions become of even greater importance in the face of the realisation that there is still much that is unknown by the various institutions of knowledge in their attempts to plumb the depths of the mysteries of man and the environment. Society today is a paradox. It is the epitome of good health - evidenced by the immense technological progress over the last couple of decades, the space age, ground breaking discoveries, etc and yet it appears on the brink of imploding - evidenced by poverty, war and consumerism. How did it all go wrong?

The list of questions can be endless, but inevitably they are all tied in to a common theme - the origin, purpose and future of the human being in the cosmos. As it is today, humanity finds herself in real danger of completely missing the big picture as she concentrates on moving further and further down the path of the individual disciplines in search of the Holy Grail. What should be done to correct this imbalance?

I'll stop at this point and open the floor to comments. I must point out that this blog is somewhat of a teaser. All the questions have answers, no surprise there! However, the point of this blog is to emphasise the fact that HEP and indeed any other discipline in any of the institutions of knowledge exists only to serve demand. And so perhaps the key for maximizing the potential of HEP would depend on understanding fully what demand entails.

22 June 2007

The Bubble Chamber Football Tournament (including results)

Post by Yoshi This year's Bubble Chamber Football Tournament is on Saturday 23 June, at UCL's training grounds somewhere in North London.

This year's Bubble Chamber Football Tournament is on Saturday 23 June, at UCL's training grounds somewhere in North London.

The tournament was inaugurated decades ago by university groups in the UK who worked with Bubble Chambers, the main tool used in particle physics experimentation in the '60s and '70s, which provided the most stunning images of particle interactions.

The participants are, allegedly:

UCL x2

Bristol

Imperial

Manchester

Birmingham

Cambridge

Exiles?

Misfits?

You could say it is a bit like the Ivy League, except it is proper football and Bubble Chambers are a lot cooler than Ivy.

Neither of the two American universities that I have been associated with in the past, MIT and Stanford, are in the Ivy League, and definitely had a long history of working with Bubble Chambers.

I am sure that if they would like to send some teams over to the UK next year, they would be welcome to join the Bubble Chamber group of universities!

The Imperial team has been practising for the last few months, every week on Wednesdays. I can't say much more here, because our formation and free kick strategies are top secret, but I'll just say that with his dazzling white boots, smart kit, and incredible pace, you might have thought that Wayne Andrews was playing for us on the wing. Just don't tell the other teams that he (our winger, I mean) is a donkey!

Saturday was a great day out, with all the teams arriving more-or-less on time and the weather holding out till just before the final kick of the afternoon.

We started out losing 1-0 to Bristol in the first match of the group stage, but since this was the first time the Imperial team had actually played together ("practice sessions" notwithstanding), we weren't too disappointed. The Bristol players had clearly met the rest of their team before Saturday.

The highlight of the day was the Central London Derby, our second match, which ended

Imperial College London 6 - 0 UCL

Personally, I think it was my tight man-marking of their right winger (and goalie) "J.B." which ensured our clean sheet.

We then went on to beat Manchester 2 - 0, and at the end of group stage the table ended up like this:

Pts GD

Imperial 6 +7

Bristol 6 +2

Manchester 6 +1

UCL 0 -10

After this some more matches were played, Birmingham won, and Cambridge (not UCL) got the wooden spoon, known (for purely historical reasons as far as I could tell) The Troll.

After this some more matches were played, Birmingham won, and Cambridge (not UCL) got the wooden spoon, known (for purely historical reasons as far as I could tell) The Troll.Next year's tournament will be at Manchester, to which there are cheap direct flights from Boston....

Posted on

Friday, June 22, 2007

3

comments (Read/Add)

![]()

Labels: bubble chamber, football, ivy league, wayne andrews

11 June 2007

SciBooNE or: How I learned to stop worrying and love the MRD

Post by Joe

After many months of cajoling, I feel that I should write a blog entry on what I have been doing whilst living out here in the USA other than enjoying their fine beers, moderately sized meals and small economic vehicles.

I suppose I should first explain how I came to work on SciBooNE in the first place. In January 2006 I joined the T2K group my supervisor, Morgan Wascko, a new lecturer joining the group. As it turned out Morgan was also co-spokesperson on the SciBooNE experiment which at that stage was a proposed experiment to be built out at Fermilab to measure sub-GeV neutrino cross-sections of interest to T2K. After some discussion it was decided that this would be a good opportunity for me to get some hardware experience by going out to Fermilab and helping in the construction of one particular element of the detector, namely the Muon Range Detector (MRD).

The MRD is an iron-scintillator sandwich detector consisting of 13 alternating horizontal and vertical layers of counters separated by 5cm of iron. The total depth of iron in the detector is 60cm which corresponds to stopping a 900MeV muon. The purpose of the MRD is to measure the energies of muons produced in neutrino interactions, for example charged current quasi-elastic (CCQE), where a muon and a proton (muon neutrino) or neutron (muon anti-neutrino) are produced. By measuring the muon energy the neutrino energy can be reconstructed.

In May 2006 I visited Fermilab for 1 month to construct and test the prototype counter design for the MRD. By June the design had been approved and mass counter assembly could begin.

I returned to Fermilab in July this time to assist in the full counter assembly which got underway at the beginning of that month. With 362 counters to be made and 3 days needed for each counter to be produced this would be the largest single job for the MRD construction. The final counters were finished in December just in time to begin the detector assembly in January. At this stage it was decided that I should move to the States to help complete the detector construction and to see it through the beginnings of its data run.

The MRD is a unique detector in the fact that it is almost completely constructed from previously used materials. The scintillator panels (20cm x 155cm x 0.6cm) were taken from an earlier Fermilab experiment whilst 5 different photomultiplier tube (PMT) flavours are used to readout these counters. The iron having enjoyed a number of years outside in the elements had to be cleaned before it was ready to be used. Even some of the cables, both high voltage and signal, had been previously used. When it came to inspect these cables, in storage in a disused detector hall, they were found in a mess, you could say a ratsnest, not so much because the cables were tangled but rather a ratsnest! As 2 grad-students went about untangling the cables two 'rats' (though they could have been large mice) emerged from their makeshift home. Needless to say this added considerable time to the cable inpections as every inch had to be checked for damage and a number were rejected having been partially chewed!

The PMTs have a range of ages, from relatively new tubes used in the KTeV and NuTeV experiments, to RCA tubes that date to the early 70's and no doubt have been used in a number of different experiments over the years. As you can imagine this produces particular problems when it comes to understanding your detector efficiencies. It is a credit to all those involved in the construction that when the detector was switched on in May 2007 only 3 of the 362 channels were found to be dead, well below our expectations.

In January the detector construction got underway in Lab F on the Fermilab site. At this stage SciBooNE, a supposedly small experiment, was starting to sprawl. Office spaces could be found in Wilson Hall, the CDF trailer and the main CDF building. As for the detector construction, the CDF pit was devoted to SciBar and the EC whilst the MRD had spaces at Lab F and Lab 6 not to mention cable repairs taking place at the D0 hall and the civil construction of the SciBooNE hall in the Booster neutrino beamline. SciBooNE was maturing fast and with the aggressive schedule put forward the hope was to see a completed detector by early June in time to commission before the proposed shutdown in August.

The MRD construction proved to be a challenge. Initially the first few planes proved trivial to construct. However as more and more planes were added to the frame so the space between planes diminished. By the time the detector was completed the space between planes was 30cm (the depth of a fermilab standard issue hardhat!) Unfortunately by this stage the american portions had got the better of myself and Nakaji (nickname: 'The Blackhole') and so it was to the smallest of our collaborators, Kendall Mahn (5' 2") to complete the work. We looked on eating doughnuts (raspberry cream I believe).

The detector construction was completed in March and was partially cabled allowing us to test the DAQ system with one week of cosmic data. The move date was set for 23rd April, and so it was apt that "Once more into the breech" was mentioned more than once that day as a 360 ton crane lowered, i've been told i'm not allowed to say dropped, the MRD into place. SciBar and the EC were lowered 2 days later.

At this stage a number of tasks in the detector hall had to be undertaken and it was hoped that the MRD cabling would begin around the 25th May and be completed by early June. However with NuInt, a neutrino interactions conference, to be held at Fermilab from 30th May until 3rd June it was with a last gasp of energy that we pushed to complete the cabling early so as to show beam events at the conference. As you can see from Morgans post we succeeded in doing so but I think it is an astonishing feat that we completed the cabling of the detector on the 24th May, 1 day before we were meant to start!

I hope this has given you a little insight into SciBooNE and the MRD, I personally feel that it is astonishing that such detectors, both SciBar/EC and the MRD, can be constructed in such a short space of time. In a little more than a year a detector went from merely a blueprint with a counter design that had yet to be confirmed as suitable, to a detector taking data. SciBars timeline is equally incredible given that it was shipped in from Japan and had to be reconstructed with a new support frame and DAQ system. It has been a great experience to work in such a dynamic collaboration, I hope this continues. All SciBooNE collaborators must be congratulated for all their hard work.

P.S. I am in the process of making a website where I will be posting photos of the MRD construction among other things T2K/SciBooNE related. I will post a link in due course.

Posted on

Monday, June 11, 2007

0

comments (Read/Add)

![]()

08 June 2007

First Neutrinos in SciBooNE

Post by Morgan I am the co-spokesperson of SciBooNE, Fermilab's newest neutrino experiment. We have a small detector with fine-grained tracking capability (for a neutrino experiment) placed 100m from the beam target of the Booster Neutrtino Beam, which is the same beam that sends neutrinos to MiniBooNE. We've just crossed the latest and most exciting of a series of significant milestones: recording our first neutrino events! Early last week, our Run Coordinator Masashi Yokoyama from Kyoto University, led the SciBooNE graduate students on an all-nighter so we could record a neutrino event or two in time for the NuInt07 conference at Fermilab. The results were fantastic, and one example is shown at right.

I am the co-spokesperson of SciBooNE, Fermilab's newest neutrino experiment. We have a small detector with fine-grained tracking capability (for a neutrino experiment) placed 100m from the beam target of the Booster Neutrtino Beam, which is the same beam that sends neutrinos to MiniBooNE. We've just crossed the latest and most exciting of a series of significant milestones: recording our first neutrino events! Early last week, our Run Coordinator Masashi Yokoyama from Kyoto University, led the SciBooNE graduate students on an all-nighter so we could record a neutrino event or two in time for the NuInt07 conference at Fermilab. The results were fantastic, and one example is shown at right.

The picture is a top-view event display of our first neutrino interaction with energy deposited in all three detector subsystems. The green field at left represents the SciBar detector, which is made of plastic scintillators with wavelength shifting fibers read out by multi-anode PMTS. The traced square and rectangles in the middle represent the Electron Catcher (EC), which is a lead/scintillating fibre EM calorimeter. The beige strips with small green trim at right represent the Muon Range Detector, which is made of 5 cm iron planes interspersed with plastic scintillators paddles read out by 2-inch PMTs. Maybe Joe will write a blog entry to describe what the MRD does; he knows all about it since he built it! Anyway, the event appears to be a single mu+ track from a muon-antineutrino. In the display, the red dots in SciBar represent strips that registered PMT hits, and the size of the dot is proportional to the amount of charge recorded. The horizontal blue and red lines next to the EC show the amount of charge read out by the EC PMTs (the EC modules are read out on both sides) and are consistent with a MIP. The MRD squares represent scintillators that were hit; we can see that the muon penetrated at least 7 of the iron planes.

Although we have identical readout systems for the side view, we were not running those channels when this event was recorded because the cooling systems were not yet fully operational. They are operational now, and we should be ready for stable beam operations by early next week.

It's a very exciting time for SciBooNE!

Posted on

Friday, June 08, 2007

0

comments (Read/Add)

![]()

21 May 2007

R-ECFA Meeting 11-12th May

Post by claire timlin ECFA stands for European Committee for Future Accelerators. The committee visits institutes in its member countries to assess the current status of accelerator physics and make suggestions on how things can be improved. I was invited to give a talk at a recent Restricted-ECFA meeting that was held at Imperial. They wanted to get an idea about what PhDs in particle physics are really like, so gave a talk about what I had done during my PhD, why I did one in the first place and what my future plans are. It was a lot of fun to stand up and give a talk that was all based on opinion (so I couldn’t technically get anything wrong!). I told them that I thought the atmosphere at CERN was great and that everyone who works there is really enthusiastic. I also said I thought the funding for PhD students was set a quite a reasonable level, sorry to anyone who thinks I should have used the opportunity to campaign for more cash. I had a few complaints, mainly about PPARC admin department (all PhD students have a story or two to back this up) and GSEPS (transferable skills courses) which are generally a waste of time. In the main I think I am lucky to be working in such an interesting and diverse field, especially at such an important time, so that’s what I told them.

ECFA stands for European Committee for Future Accelerators. The committee visits institutes in its member countries to assess the current status of accelerator physics and make suggestions on how things can be improved. I was invited to give a talk at a recent Restricted-ECFA meeting that was held at Imperial. They wanted to get an idea about what PhDs in particle physics are really like, so gave a talk about what I had done during my PhD, why I did one in the first place and what my future plans are. It was a lot of fun to stand up and give a talk that was all based on opinion (so I couldn’t technically get anything wrong!). I told them that I thought the atmosphere at CERN was great and that everyone who works there is really enthusiastic. I also said I thought the funding for PhD students was set a quite a reasonable level, sorry to anyone who thinks I should have used the opportunity to campaign for more cash. I had a few complaints, mainly about PPARC admin department (all PhD students have a story or two to back this up) and GSEPS (transferable skills courses) which are generally a waste of time. In the main I think I am lucky to be working in such an interesting and diverse field, especially at such an important time, so that’s what I told them.

Many people gave talks concerning the state of physics in schools, funding for research and general overviews of experiments and institutes. The committee returned a very positive verdict about the status of physics in the UK and made some constructive suggestions. They commented on the small proportion of women in the field but accepted that redressing this balance is a complicated, long term process.

14 May 2007

Rector supports blog

Post by Patrick

Last Friday Imperial's rector Sir Richard Sykes visited CERN - in particular the two experiments with IC involvement CMS and LHCb.

The visit was supervised by CERN's VIP service, a guarantee that nothing can go wrong: 9:00 pick up at the hotel, 9:25 arrive at LHCb, visit. 9:45 go to CMS, photographer is waiting... and so on until the signature of the guest book at 14:15 (involving another photographer). A quite impressive organization that has not much in common with the usual "private" visits of LHCb or CMS.

So early in the morning Jim and the rector met us (Tatsuya, our spokesman, Will and myself) at point 8 for a visit of the LHCb detector. Tatsuya showed every interesting detail and let us enter any usually forbidden door. A quite interesting tour, even for LHCb members! Of course we had a long stop in front of RICH1 where I tried to explain how it works (remember Cherenkov radiation?) and why we need such a device and CMS don't. I also took the opportunity to ask him if I could make a picture for the blog. That's when he said it was a great idea. One needs to be modern...

Of course we had a long stop in front of RICH1 where I tried to explain how it works (remember Cherenkov radiation?) and why we need such a device and CMS don't. I also took the opportunity to ask him if I could make a picture for the blog. That's when he said it was a great idea. One needs to be modern...

After a brief visit of the LHC tunnel we left Tatsuya and Will and continued to point 5 for a CMS visit. Since I hadn't seen CMS for quite some time (especially not since there's something in the cavern) I joined the CMS tour - which was really impressive. Not only because of CMS, but mostly because Jim knows every detail of it and seems to remember an anecdote about every piece of equipment. He also seems to remember each price tag... The morning was quite challenging - the rector - a biologist - had many interesting questions and seemed very interested about the goals of the research and the technical challenges. I am also not used to being followed by a professional photographer all the time!

The morning was quite challenging - the rector - a biologist - had many interesting questions and seemed very interested about the goals of the research and the technical challenges. I am also not used to being followed by a professional photographer all the time!

We then went to CERN for a lunch with Lyn Evans - head of the LHC project - and Geoff (who would later show the CMS tracker). Of course I tried to get a few insider information about when the LHC will start, but the official statement remains: there will be an announcement by the end of the month. (But feel free to drop by my office I you want to hear some unofficial statements).

Posted on

Monday, May 14, 2007

0

comments (Read/Add)

![]()

01 May 2007

Must See TV Tonight

Post by Yoshi Apologies to our vast international readership who do not have the privilege of paying the BBC licence fee, but tonight there will be a programme on BBC2 at 9pm, called, ahem, Horizon: The Six-Billion Dollar Experiment.

Apologies to our vast international readership who do not have the privilege of paying the BBC licence fee, but tonight there will be a programme on BBC2 at 9pm, called, ahem, Horizon: The Six-Billion Dollar Experiment.

Yes, it is about the LHC.

Since there is absolutely nothing else on the telly tonight, I am sure the whole nation will be captivated by this programme.

Among the questions to be answered tonight:

- Will the BBC get the physics right?

- Might the LHC create a black hole which will gobble up the planet (a question that I was asked at passport control last month!)

- Will anyone tell them that "the God Particle" is a really really useless name for the Higgs? (with all due respect)

- Will any of our colleagues at Imperial HEP appear?

- How will Peter Crouch do against John Terry and Michael Essien?

Posted on

Tuesday, May 01, 2007

11

comments (Read/Add)

![]()

Labels: black hole, champions league, chelsea liverpool, destruction of the earth, horizon, lhc

15 April 2007

The IOP conference

Post by Tom This years IOP conference took place from the 3-5 April at the University of Surrey . For anyone who's not familiar with the conference it's aimed at getting all the final year students to give a conference talk before the end of their PhDs. It's also a very good excuse to get the students and lots of the staff from all the groups over the country together for a few (!) drinks.

This years IOP conference took place from the 3-5 April at the University of Surrey . For anyone who's not familiar with the conference it's aimed at getting all the final year students to give a conference talk before the end of their PhDs. It's also a very good excuse to get the students and lots of the staff from all the groups over the country together for a few (!) drinks.

Somehow, and I'm still not sure how, I managed to end up responsible for everyones paperwork. For any current second year students out there I'd avoid this at all costs! It took 24 forms, one lost cheque and a lot of chasing but finally we were registered.

The week before the IOP conference we're expected to give a practice run in front of the group at Imperial. I think it's fair to say that whilst this was incredibly useful it was also totally disheartening, probably for the staff as well after 7 hours! The most important lesson for me seemed to be that as I'd gotten used to giving collaboration talks I'd also picked up some really bad habits. The biggest criticsims, providing far too much information on the slides and my use of complete scentences.

The real thing, strangely, was a lot less scary (even in the main lecture theatre) and despite all my complaints beforehand about ending up in a session with mainly ZEUS students, I actually really enjoyed it. In fact the talks I enjoyed most were nearly always from the running experiments. I guess it's good to see something other than MC studies for once. The downside was that everyone was there for these talks and few people showed interest in the two LHCb talks tagged on at the end.

It was really good to catch up with everyone else in my year and I've probably learnt a fair bit from all the talks but I'm glad it all only happens once!

Posted on

Sunday, April 15, 2007

2

comments (Read/Add)

![]()

12 April 2007

Bye Bye Imperial College

Post by FreyaFriends and family are sometimes amazed when I describe how the career path in particle physics works. I think this is quite an interesting subject and also different than many other careers, so I thought I would create a post on this. This is particularly relevant as I have just changed jobs. So for this one time we will not talk about physics but instead about what it is like to do physics.

Particle physics is a very international field. For example I grew up in Amsterdam, the Netherlands, where I also did my undergraduate studies. When I graduated I decided continue study for my Ph.D. in Amsterdam, at NIKHEF. About half of my five-year Ph.D. I spent in Chicago, working at Fermilab. Once I received my Ph.D. I accepted a contract for two years at Imperial College, as a research associate. Young researchers that are not lecturers or readers yet are usually referred to as Post-docs. This has to do with the fact that they already have their doctorate. I recently accepted a more advanced post-doc position with Cornell University. Even though Cornell University is based in Ithaca, New York, USA, I actually will live and work in Geneva, at CERN. The next step in my career probably would be to become a member of staff at some university. I am very much looking forward to that, as it would involve teaching and working with students.

One of the interesting things is that during all this time I was working in large international collaborations, so there really is not much difference except for the location and your direct colleagues. I think that if you ask a random particle physicist they will tell you that their work is so international that location really does not make a difference any more. I now have just started a new job and besides having moved to a different country the only change I've noticed is that being closer to the detector project I work on makes life much easier. Oh and the fact that the weather is better in Geneva, of course!

I love my job and the traveling is one of the additional advantages (besides doing something fun, interesting, challenging, with motivated colleagues in an international environment)

Posted on

Thursday, April 12, 2007

0

comments (Read/Add)

![]()

Labels: Physics career NIKHEF CERN

11 April 2007

Opened Box

Post by Morgan

Well, the big moment is about to arrive. More than a decade ago, the LSND collaboration shook up the particle physics world by announcing a neutrino (actually, antineutrino) oscillation result whose interpretation requires physics beyond the standard model. As I wrote in a previous entry, I am on MiniBooNE which has been working on a blind analysis to confirm or refute the LSND result for the past ten years. We have been pushing very hard to "open the box" and see what the answer is for quite a while and it has finally happened.

Our box opening procedure was a four step process in which each step was designed to reveal enough information that we could decide if things were working correctly, but not enough information to tell us the answer. Thus blindness was preserved until the final step. Our procedure was designed so that if a problem were to be found in one of the early steps, we could stop the procedure and try to fix the problem, before starting over again. Doing that would be OK as long as we did not reveal any information about the contents of the box.

Today at Fermilab, our first oscillation result will finally be announced, and tomorrow I will give a seminar on the result myself here at Imperial. I can't say what the answer is yet, so you'll have to come to my seminar to find out!

As an interesting side note, we did have to stop the box opening procedure and start over again, so it was a very good thing that we had this procedure. We attempted a box opening in February, over the weekend when I wrote my blind analysis blog entry, and discovered a reason to abort the process and regroup. But a full entry about that will have to wait until the result is announced to the world. Right now, I have to complete my seminar!

Posted on

Wednesday, April 11, 2007

2

comments (Read/Add)

![]()

Labels: blind analysis, neutrinos, oscillations

08 April 2007

Big Bang exhibition at the Science Museum

Post by PatrickSome time ago I wrote about Fieldwork for the Science Museum and promised some updates. Back in February we were trying to repair an old spark chamber for an exhibition about the LHC at the Science Museum. The exhibition is now open but the spark chamber isn't there.

Dave spent a lot of time trying to repair the spark chamber and there is still a hope that it will go to the Science Museum. But it missed the deadline for the exhibition opening. The problem was with the trigger. The chamber is activated by two huge scintillators which produce a signal when a charged particle crosses. One is mounted below the chamber, the other is on top of it (it's the kind of gnu horns you can see on the picture in the original post). All the light guides (that guide the scintillation light to the photomultipliers) are broken. They can be repaired but that takes some time. Dave is working on that. As for the chamber itself, it looks OK. It produces nice sparks when activated by an almost random trigger.

The exhibition is essentially a huge cube of 5m size explaining in four zones what the LHC is about, how it works, how the detectors work and how the data will be analyzed. Or, well, as the exhibition is aimed at 14 to 17 year olds, it does not explain that much but gets a feel for how complicated and huge it is. The exhibition is actually called Big Bang (and that's what you'd read from the distance), as it's about recreating the conditions of the Big Bang in a laboratory. The illustrator made a great job drawing particles and collisions. I love his drawing of a cavern with all the ongoing activity! I won't say more. Come to the Science Museum (it's free) and see it.

The whole design process started (for me) in December where I attended a day long brainstorming session with 20 more physicists from various places in the UK. The team from the Science Museum was quite impressive at extracting as much information and ideas from us as they could. Of course many of them were not feasible, like putting a 1:1 picture of Atlas on the wall (rejected as it wouldn't fit: the museum is much too small!) or putting a real Grid node in the museum. Instead there's a lot of graphics, animations and small movies.

Then for several months we got spammed by the designer teams sending us text snippets to check for scientific accuracy. A month ago there was a meeting with the designer who explained us his ideas for the layout. Scientists and designers: two worlds collide... But we eventually managed to speak a common language.

Three weeks ago I got a mail asking if I was happy to be quoted in the exhibition saying "These high-energy collisions will replicate the conditions that occurred in the moments after the Big Bang, 13 billion years ago". I don't remember having ever said that and would have said 14 anyway... They obviously got a lot of quotes from the brainstorming session and wanted to match them with real scientists. So I agreed provided they change the age of the Universe (!). The result is shown in the picture.

Posted on

Sunday, April 08, 2007

1 comments (Read/Add)

![]()

Labels: exhibition, lhc, science museum, spark chamber

01 April 2007

The National Particle Physics Masterclass

Post by PatrickLast Wednesday we organised our traditional annual masterclass (see web-page). Practically this means we invite 120 A-level students having chosen physics as one of their main subjects (and therefore hopefully interested) and talk about particle physics during an afternoon.

We had four lectures about antimatter (Patrick), Higgs searches (Gavin), neutrino oscillations (Yoshi) and solar neutrinos (Dave) and a discussion session where students could ask a lot of questions ranging from "Why do you like particle physics?" to "Can you explain Bell inequalities in 5 minutes?". If there's any question still unanswered don't hesitate to post it on this blog using the "Read/Add comments" link below.

The masterclass went quite smoothly, given that the air-conditioning decided to die during the morning, which forced us to reshuffle the order of the breaks a little. There's no real fun if there's not a little touch of improvisation in the organisation!

I had a first look at the feedback questionnaires. The students most liked the discussions and Dave's talk. We also had a lot of praise for the catering.

Among the suggestions for improvement of course the air conditioning was mentioned, as well as a need for more breaks (we'll take that into account for next year for sure!). Then we had a lot of of interesting but sometimes contradictory suggestions for "more" and "less theory", "more demonstrations" (yes, I agree, but that's difficult to organize) and "some derivations" (that's a tough one...). Many thanks to the students for all the useful feedback!

I would also like to thank all my colleagues who worked to make this happen: First Piera for all practical aspects. Paula and Ghislaine for the help with the catering. The already mentioned speakers of course, and everyone who joined the discussions. I can't possibly cite them all here!

Posted on

Sunday, April 01, 2007

2

comments (Read/Add)

![]()

Labels: master-class

27 March 2007

Un altro litro di vino rosso per favore

Post by MattCiao tutti; no doubt you have already guessed where I am. That's right, I'm in Slovenia, trying to hunt down that accordion player who kept us awake all weekend at our hotel near the ski resort of Cervinia.

No, not really. I am, of course, in Rome, my most favourite of eternal cities. My purpose here is twofold (threefold if you take into account my insatiable appetite for saltimbocca and pan-fried ciccoria).

Firstly (and in reverse order) for the second half of the week I'll be attending a CMS ECAL testbeam workshop at Rome University. The workshop has been organised to review testbeam activities over the past few years, discuss results, and, I suppose, ponder how what we have learnt from these programmes can feed into the first operational phase of CMS later this year. For myself, I'm going along to glean as much information as I can in preparation for our ECAL Endcap testbeam in a couple of months.

Secondly, for the first half of the week, I'm visiting my colleagues at ENEA (CERN canteen: please please please be more like the ENEA canteen). I've been working with them on how irradiation affects the uniformity of the ECAL's lead tungstate crystals. Unfortunately, the programme of research we envisaged has been plagued with problems. Initially with the photodetector I brought from Imperial and then a bigger problem with the ENEA gamma ray source which took several months to fix (you can't just walk in there with a screwdriver). But that's the way it goes sometimes in all fields of research and now we have to get on with the information we have and focus on completing the endcaps for the first LHC phyics run next year.

ENEA have also been producing supermodules for the ECAL barrel and tomorrow we'll have a ceremony marking the completion of the final supermodule. I've packed a nice shirt and smart trousers for the ceremony (I've ironed the shirt mam) and I'm looking forward to the good food and wine that invariably accompanies such celebrations in Italy. It's very exciting (yes, I admit it) to see the detector very near to completion, but, I suppose, also a little sad as all the small collaborations that were formed over the years to build the thing start to dissolve.

Ah well. I'll be consoling myself in Da Lucia in Trastevere this evening with some spaghetti alla gricia and maybe I ought to try the tripe (a Roman speciality). I quite enjoy dining alone. Once the initial acute self-consciousness is conquered and the first half-litre of wine given a good home, it's pleasant to watch the other people in the restaurant (especially the struggling tourists discovering Italian cuisine has nothing to do with Hawaiian pizzas and spaghetti bolognese). Oh and one last thing; should the nice girl at the Hotel Posta near Cervinia be, by some amazing chance, reading this, I meant to say something really funny and not mumble "arrivederci" and my phone number is 004176...

Posted on

Tuesday, March 27, 2007

0

comments (Read/Add)

![]()

25 March 2007

D Zero week

Post by Nicolas OsmanA few weeks ago, the D Zero experiment had its collaboration meeting. As I have just started my PhD, this was my first time at the experiment, and indeed my first time in America! It was a bit of an adventure, which is why I have taken so long to write about it (I needed to recover first), but it was a good experience.

About D Zero itself; D Zero is a general purpose detector for the Tevatron accelerator. The laboratory (Fermilab) is essentially built in a nature reserve; originally, the land was all arable fields, but now it has been reclaimed as prairie land (complete with buffalo, coyote and all sorts of other animals). Obviously, it was fairly cold out there, but I was quite happy - until I 'found' that frozen stream, that is.

It was good to meet the people who work on D Zero; I have done Summer work at CERN in the past, and I found the atmosphere at the two laboratories is very different. I learnt a lot about the experiment itself, as well as how the collaboration works.

I was also able to spend some time in the city. I like Chicago a lot, especially the beach, the Art Institute and the Millennium park. I had a rather unfortunate experience at Lincoln Park Zoo, but it would be best not to go into details here.

Overall, I really enjoyed the whole trip; it was very valuable to me, and now I have a clearer idea of where my PhD is going.

Posted on

Sunday, March 25, 2007

0

comments (Read/Add)

![]()

20 March 2007

Mother Nature's Bumps

Post by Yoshi Last week, Dr Sam Harper visited us to talk about his PhD work at the CDF experiment at Fermilab.

Last week, Dr Sam Harper visited us to talk about his PhD work at the CDF experiment at Fermilab.

Sam was an undergraduate student at Imperial HEP before he moved to Oxford to do his PhD (or whatever it is they call them), so it was a bit of a homecoming for him.

The talk was about a study of events at the Tevatron collider with two prominent electrons/positrons emerging from the collision of protons and anti-protons. This is a channel with good sensitivity to New Physics, because the events themselves are clean and well-defined, the expectation from the Standard Model is well understood, and because if there is something New that is contributing to the events, you can use the electrons to figure out its mass, although that does depend on the way the New thing turns into electrons.

Sam went through the different aspects of the work, from the motivation and analysis procedure through to the final "mass spectrum" that he found from the electrons. It is the mass spectrum which encodes any signs of New Physics, and in particular, any unexpected "bumps" in the spectrum (there is only one you expect to see, a huge bump at 90 GeV due to the "Z boson" discovered a couple of decades ago at CERN) would be a smoking-gun signal, if significant. For an example of an undisputed, definitely significant, unexpected bump in the equivalent type of event, at the high energy frontier of more than three decades ago, check out the J particle discovery mass spectrum!

For an example of an undisputed, definitely significant, unexpected bump in the equivalent type of event, at the high energy frontier of more than three decades ago, check out the J particle discovery mass spectrum!

Getting to the mass spectrum was just two-thirds of the talk though. Because events occurring in the detector gradually build the mass spectrum up over time, there is always going to a be an inherent bumpiness in the spectrum at any one moment. So the rest of his talk dealt with a full statistical analysis, which demonstrated how likely it was to see such "accidental bumps" in the spectrum and of what size. The human eye has a natural tendency to see patterns even when there is nothing there, so you need an objective analysis like this to tell you if there might be something New there or not.

Whether there are any significant bumps, and other details of the study can be found at Sam's home page for the analysis.

All of this did remind us of other "bumps" in Tevatron data which have been the recent focus of discussion in physicists' blogs and the popular press.

The moral of this story is I think, that when Mother Nature responds to the questions you have asked her, listen carefully, and don't pick and choose from her answers....

Posted on

Tuesday, March 20, 2007

0

comments (Read/Add)

![]()

Labels: 160 GeV higgs, CDF, di-electron, mass spectrum, resonance peak

The moral of the story is...

Post by Ian

I was asked last week, by an American friend and colleague, whether London had any bad parts of town. I was a little surprised by the question, she has been visiting us here fairly regularly over the last 9 months, and I assumed she would have realised that, like all big cities, London has it's parts that you shouldn't wonder into. Still, I told her about my first flat near Finsbury Park, how Abu Hamza used to live and work near by, and how my flatmate would always finish his run a couple of minutes faster if he did it after dark. I even mentioned that one of the big delivery companies (DHL, I think) would deliver parcels all over Iraq, but would still avoid parts of E16, my current post code. At no point however, did I think to mention the dangers of Oxford Circus...

As most people know, last Saturday was St Patrick's Day and being an avid fan of the black stuff, I decided I wanted another St Patrick's Day Guinness hat. I got one in 2005, but it never really fitted, so I hoped that by 2007 this design flaw would be sorted. So I meet up with some old friends from my undergrad days, and we go to a nice pub called the Marlborough Head, near Bond Street station. We have a leisurely lunch, during which time I drink 2 pints (half way to my hat) and then we go off to do a little shopping (or get a hair cut in my case). About 3 hours later, we go back to the same pub, have a few more pints, watch Wales beating England at rugby (shame!) and some light pub food to tide us over till dinner.

At just gone seven, we leave the pub, Niall and I proudly wearing are hats, and decide to go to the Apple shop, on Regent Street before heading home. So we march of down Oxford Street, getting funny looks from some, amused glances from others and, unfortunately, undue attention from a rather inebriated Polish guy with a bottle of wine. It's something that seems to happen any time that one goes out in public wearing a silly hat, people come up to you, shout some appropriate phrase in you face and wonder off, all harmless and part of life. This guy, didn't wander off however, he wandered down Oxford Street with us, still yelling and the like, until we reached Oxford Circus. As we turned South, down Regent Street, I kind of hoped that we would part and it would just become another funny story, but alas he decided to keep following us, keep bumping into us and keep being a nuisance. So I asked him to leave us alone. He was 'disinclined to acquiesce to my request' and after being asked a second time decided to take a swing at me.

This is where things get a little hazy, I remember being hit (didn't really hurt), I remember swinging him into a wall (broke the bottle of wine) and I remember him deciding the neck of the bottle wasn't much use without the rest of it and he may as well throw it at my head. In all honesty, that didn't hurt much either, but seeing as we were both bleeding it seemed a fairly good time to stop fighting (personally, I don't think it was ever a good time to start...) and my friends led me off to find medical attention. One short taxi ride (and about 2 packs of tissues) later and I'm in University College London Hospital waiting for an X-ray and some patching up.

During my stay there, I find out that the wound is free of glass fragments (yay), my assailant has been brought to the same hospital and is now talking to my friends, not realising who they are (ahh), hospital security go past wearing stab proof vests (double ahh), the police arrive (better), ask me if I want to press charges (yep), I get patched up/flirted at by a cute nurse (yay, wait, I mean... 'I'm in a serious relationship') and give a description of what happened to a cute young police lady (not a statement, because I'd been drinking).

Three days later, the bandage that you can see in the photo has been removed, and more glue has been added, so that my ear now looks like this (little warning, not a particularly pleasant photo).

So, the moral of the story? I don't know really. It's not to avoid Oxford Street, that's for certain. Don't wear silly hats in public is a maybe, but many others seemed to enjoy that night. Don't drink sounds good, but I was far from drunk and little would have change if I was completely sober. I'm not even sure if there is one, but if you can think of a good one, feel free to comment...

Posted on

Tuesday, March 20, 2007

2

comments (Read/Add)

![]()

Labels: bottle, Oxford Street, UCL

17 March 2007

Winter Seminar in Austria

Post by AjitThis seminar was organised by the Institute of Applied Physics of Frankfurt University and is the 25th year that they've been doing this. The venue was a lodge, owned by Frankfurt University, about 200 miles away from Frankfurt in a region called Kleinwalsertal just over the border in Austria.

I have to say that I was a little bit unsure as to how the workshop was going to go, seeing as most of the talks were going to be given in German and I only know a few words of German. However, I was reassured that the slides were going to be in English. In the end I found most of the talks quite useful and it was good to meet other people working on similar projects to the one I'm working on. As is usual with this type of meeting there was a strong work hard/play hard ethic. The day from 9am to 5pm was free so that people could enjoy the local scenery and make use of the skiing facilities. Talks then started from 5pm and went on until about 10pm (with a break at 6pm for dinner). I've always wanted to try a bit of snowboarding so this was going to be a good opportunity! Four other students from Frankfurt and I booked ourselves on a 3 day snowboarding course. And so over those three days I became acquainted with how to land on my bum, with a snowboard strapped to my feet, in various snow conditions: hard snow, ice and wet slushy snow!

By the end of the first day I could go fairly quickly down the slope but hadn't mastered braking so would have to do a controlled crash kicking up large amounts of snow in the process. At one point a little girl skiing past offered to help me up (at least I think that's what she meant, she was speaking in German). I politely declined! By the end of the second day I'd managed to master braking but only if I was on the front side of my board (i.e. facing backwards). If I wanted to turn right I was in trouble! By the end of the third day I managed to master turning right and getting my balance on both the front side and back side of the snowboard. I was feeling confident enough with my abilities that I took a short video on my digital camera as I came down the slope!

This meeting wasn't all play though. As I said talks went from 5pm until 10pm and after a days snowboarding keeping concentration was tough. Everyone else at the meeting was from a German institute and so the talks gave a nice overview of the accelerator physics projects happening at various institutes across Germany. It was very useful to find out about other projects that are similar to the one I'm working on (The Front End Test Stand) since there is no project even vaguely similar to ours in the UK. I gave an overview of our project and showed my little snowboarding video at the end of my talk, which went down very well! I thought there'd be a few awkward questions since there were many experts in the audience and I'm really learning on the job (you find a lot of that in particle physics, i.e. having to learn something whilst at the same time having to implement that method or theory!). But, everyone was incredibly positive and some people felt that they could also learn from what we are doing.

On the whole, it was a very useful seminar. I learnt some physics, drank some German beer, made some useful contacts, learnt about other projects, learnt to snowboard but most importantly, got invited back next year!

Posted on

Saturday, March 17, 2007

2

comments (Read/Add)

![]()

Labels: austria, front end test stand, proton driver, snowboarding

13 March 2007

First LHCb week at CERN

Post by WillI'm out at CERN for my first LHCb week. Four times a year, everyone working on the LHCb gets together to discuss how things are going with the experiment. For me, it's a great opportunity to meet lots of people, some of which I've already been working with, and some who I will work with in the future. I've been here for 5 days already, and have found my time very productive.

I have been working on a software project called Ganga, a neat little Grid front end tool used developed by members of the LHCb and ATLAS collaborations. It’s been really good to meet other people working on the project and discuss ideas face to face.

There are lots of interesting meetings scheduled this week, and today I'm off to find out about the RICH detector and the "online" software (used during data taking). Later in the week, there are meetings on Physics and computing, which I am looking forward too, and a lecture by Michael Frayn, a well known British playwright. I’ll try to post a follow up to let everyone know how the week went.

Posted on

Tuesday, March 13, 2007

0

comments (Read/Add)

![]()

12 March 2007

The PhD End-Game (Thesis/Viva) Experience

Post by JohnSo you start your PhD in HEP in Imperial by doing courses to get a grounding in the subject, work out (hopefully) what you actually want to do as a PhD during the rest of the year, spend the better part of the rest of the three years (or four, as it is now) desperately trying to create a cohesive piece of research, then bind the whole lot into a thesis. Easy.

Perhaps the strangest thing for me about writing my thesis was really trying to decide what point I was getting across. During a PhD you always end up working on a lot of different things, some of which you include and some of which have no direct relevance. Then you have a restriction on how long it should be. Mine was 170 pages, a little on the long side, but I actually left out a huge chunk of work on a medical imaging project called I-ImaS we worked on in the Silicon lab. It would have muddled the topic of the thesis, not to mention doubling its size.

In the end I decided that CMS was my primary focus, and the important work was on the off-detector trigger and readout electronics. As a CASE student I was in a slightly unusual position as my PhD was mostly about the hardware design of CMS, including the complexities of design, implementation details and possibilities for future upgrades. I also became heavily involved in designing and commissioning the Global Calorimeter Trigger (GCT), very late in my PhD. While it delayed my submission it also shifted the topics I chose to present.

Approaching things from a hardware perspective left me with an interesting dilemma when it came to the viva. What to revise? Hardware, analysis methods, trigger algorithms or more of the physics? As CMS isn't a running experiment this is more of an open-ended question than usual, and you can't know everything (there are, after all a few thousand people involved in the project for a good reason!). In the end I did a bit of everything, but (and perhaps this is due to the hardware nature of the PhD), I think that it's harder for examiners to relate to someone who's specialised heavily in hardware, as it's a less common trait in particle physics. Working on FPGAs and ASICs in Silicon requires a lot of specialised knowledge and isn't an area that's accessible to most physicists. (Incidentally, I think people often forget how lucky we are at IC to have a Silicon lab and an electronics workshop, not to mention some very dedicated and capable people to work with in both of them).

My external examiner was, (unfortunately for me!) very knowledgeable in FPGAs and the modern technologies used in CMS. I had a couple of very interesting discussions about the intricacies of 8b10b encoding in serial links... but one thing became clear during my viva. Virtually all the discussions were on topics I hadn't expected. This isn't to say that reading around the subject before the exam isn't useful, but it's worth remembering that you're partly there to be examined one what you don't know rather than what you do.

Which brings me to my conclusion on the experience. I think if you work hard, write a good thesis and contribute well to whichever collaboration you work on you'd have to work hard to fail in a viva. Your fate is most likely sealed before you even enter the room. For me I think the most useful thing about the viva was the clarification of what I didn't know. As I'm staying in research this is something I can work on!

Posted on

Monday, March 12, 2007

2

comments (Read/Add)

![]()

Labels: cms, phd viva, thesis defence

02 March 2007

T2K Workshop in New York

Post by Yoshi We are midway through a two-day workshop with our T2K colleagues, being held at Stony Brook University, on Long Island, New York. I have studied and worked at several US universities, but this campus really is the quintessential American campus for me, with windswept car parks each bigger than Imperial College, a "football" stadium, and everything being about twice the size that it needs to be.

We are midway through a two-day workshop with our T2K colleagues, being held at Stony Brook University, on Long Island, New York. I have studied and worked at several US universities, but this campus really is the quintessential American campus for me, with windswept car parks each bigger than Imperial College, a "football" stadium, and everything being about twice the size that it needs to be.

Antonin our Research Associate has come with me from London, and our students Ian and Joe are here too. Joe is living in Chicago now to work on SciBooNE, so it has been a couple of months since I last saw him. He prefers now to support the Chicago Bears compared to the misery of following the perennial 2nd Division club that he used to have an interest in. We are joined by our colleagues from UVic and TRIUMF in British Columbia, and some European universities, and of course the Stony Brook contingent. With only a couple of years to go till the T2K experiment gets going, we are working to make sure the computer software will be ready and up to the job. I will leave it to Antonin, Ian and Joe to add fair and balanced (and 99% censorship-free!) comments on how the meeting is being run. At least my choice of dinner venue was met with approval. I somehow think I will be judged on whether I will be able to bring the meeting to a close as scheduled, this being a Friday! We shall see come 6pm....

We are joined by our colleagues from UVic and TRIUMF in British Columbia, and some European universities, and of course the Stony Brook contingent. With only a couple of years to go till the T2K experiment gets going, we are working to make sure the computer software will be ready and up to the job. I will leave it to Antonin, Ian and Joe to add fair and balanced (and 99% censorship-free!) comments on how the meeting is being run. At least my choice of dinner venue was met with approval. I somehow think I will be judged on whether I will be able to bring the meeting to a close as scheduled, this being a Friday! We shall see come 6pm....

Posted on

Friday, March 02, 2007

1 comments (Read/Add)

![]()

Labels: new york, stony brook, t2k offline software

24 February 2007

Fieldwork for the Science Museum

Post by Patrick

This week I've been trying to fix a big spark chamber for the Science Museum with the precious help of Prof. Websdale. On the picture you can see him installing a scintillator on top of the chamber. I'm happy he accepted to help me because he used to build such devices in the past. I belong to the generation of particle physicist who remotely log on to a detector when it doesn't work and debug it by looking at the logfiles. In this case we use screwdrivers, a voltmeter and an oscilloscope. Something quite unusual for me...

I'm doing this because the I am LHCb-UK Outreach coordinator. As such I am supposed to coordinate the outreach activities in the UK of the LHCb experiment, i.e. explain to the average UK citizen what LHCb is doing. Since LHCb has very little manpower (to be taken as an euphemism) available for such activities there's hardly anything done. Please don't visit the public LHCb web-site, it's such a shame.

Yet as a CERN experiment we should devote part of our efforts explaining to the public what we are doing and why. CERN itself is an open laboratory with a quite decent public web-site.

What is more important in my activity as outreach coordinator is that I am part of the larger group of people who try to promote the LHC in the UK. What for? might you think, we have nothing to sell so why bother making an advertising campaign. That's the subtle difference between marketing and outreach. The UK taxpayers pay about £60M a year as a contribution to CERN and that's not counting what is paid to the research groups in the UK (my salary for instance). Some consider this as a contribution to culture: it's the price for increasing our understanding of Nature. Some might consider it as a long term investment in the future. Our economy is presently growing on the grounds laid during the first half of the past century, when quantum mechanics was developed (think of computers, mobile phones, microwave ovens, lasers...). We might be discovering now what the economy will be based on in 50 years (... or not).

In any case we owe the British public an explanation of what we do with the £1 each taxpayer spends every year to fund our research. We try to have contact with the media, we prepare material for teachers, we have set up a UK website about the LHC (here)... But we first had to find out what to tell the public. The buzzword is Big-Bang: the key message is that we are recreating the conditions of the Big-Bang in the laboratory. If you are interested in the details look at the result of the formative evaluation.

This message will also be central at the upcoming exhibition about the LHC at the Science Museum, for which I am part of the advisory panel. The exhibition will start in April and I am of course not supposed to tell you what it will show. Come and see it. There will for sure be a post here about its opening.

In order to show particles to the public the Science Museum wanted to have a "Cosmic Ray Detector" on display, a device that would show the path of cosmic rays. After some research I found out that they already had one, which Imperial College and Rutherford laboratory built for them some time ago, but that it was probably labeled "Spark Chamber" in their stores. They indeed managed to find it and now we are trying to get it operational.

Stay tuned, hopefully I'll soon be able to add another post about the successful outcome of this fieldwork.

Posted on

Saturday, February 24, 2007

1 comments (Read/Add)

![]()

Labels: lhcb, science museum, spark chamber

14 February 2007

International Collaborations, Elections, and the Subtleties of Language

Post by YoshiAn election was just held to decide who would work alongside Koichiro Nishikawa of Kyoto University as the first International Co-Spokesperson for the collaboration of a couple of hundred physicists working on the T2K Experiment.

When Dave Wark, my colleague at Imperial, was nominated as a candidate, I offered him a bit of advice to help him advance his international credentials -- through the words "yoroshiku onegai shimasu" which is what Japanese politicians spew after every other sentence during election campaigns. It roughly translates to, well, er, ...according to one web page:

"I suppose every language has a number of expressions that defy translation into another language. One of the Japanese phrases that belong to this category would be 'Yoroshiku onegai shimasu.'", then going on to say:

"Thus, if I were to be forced to translate the phrase 'Yoroshiku onegai shimasu.' into English, I would say, 'I hope you will take care of ( someone / something ) in a way that is convenient for both you and me. (I count on your cooperation.)'"

Which sounds utterly shameless in this context....

My personal translation, which is what I gave Dave, was that it expresses a desire for "the concept of pursuing goodness, correctness". Beautiful.

I think he might have used the phrase at a meeting or two, though whether anyone actually understood him is unknown.

He didn't listen to my other suggestion that he ought to become the first physicist to launch a spokesperson election campaign on YouTube, however.

But now, the speculation is over. I can sense the tension in the imperialhep.blogspot.com readership.

The results were announced earlier today, and despite not having a YouTube election campaign, it turns out that Dave has been elected by a majority of the vote.

Whether our new International Co-Spokesman will ever visit us on this blog remains to be seen. Dave?

Posted on

Wednesday, February 14, 2007

1 comments (Read/Add)

![]()

Labels: spokesperson, t2k, yoroshiku

12 February 2007

Results of Paint-o-Clock

Post by Will

So here is the final "Paint-o-Clock" output. I think it looks rather good!

For those of you wondering, the pictures are:

- A Segment of CMS being lowered under ground, with a muon chamber being fitted.

- The Wilson Hall at Fermilab

- A simulated Higgs event in CMS

- Super-K and the T2K near detector and a cosmic ray air shower.

Posted on

Monday, February 12, 2007

2

comments (Read/Add)

![]()

Labels: painting, social event

11 February 2007

Blind Analysis

Post by Morgan

I'm a member of the MiniBooNE collaboration, and we are doing a blind analysis in our search for neutrino oscillations. The idea is that we wish to prevent biasing ourselves before we complete the analysis of the data. We are doing a "closed box" blind analysis, which means that we sequester the events that appear to be signal-like and do not perform any analyses on them before the analysis chain is complete.

Our analysis is a search for electron neutrino events in a muon neutrino beam, which is the signature of neutrino oscillations seen by the LSND experiment. We are performing the experiment to confirm or rule out the LSND neutrino oscillation result. Effectively, the blind analysis means that we use other data samples, like the muon neutrino data and cosmic muon decay electron events, to understand our event reconstruction and analysis algorithms. We do not use electron neutrino events that might come from neutrino oscillations in the development of the analysis, but only after the algorithms are complete. We are currently in the final stages of the analysis, and are hoping to open the box soon, although we have been saying that for a while!

We chose to do a blind analysis for many reasons, but one of the key reasons is that the LSND result, if it is due to oscillations, would be inconsistent with the Standard Model's prediction of only three families of neutrinos. Thus, the LSND result has huge ramifications if it is confirmed and we deemed it necessary to use the most strict methods in our search for these oscillations.

As a MiniBooNE collaborator, I am often asked if we will see a signal, which is to say: do I think the LSND signal is real? I've come to realize I don't care if we see a signal. All that matters to me is getting it right. Frankly, I think it would be scientifically irresponsible for me to hold a strong opinion about it one way or the other. I think that the beauty of science comes from the idea that Nature can reveal her secrets if we ask the right questions and are open to the answers. Approaching this analysis with a strong bias one way or the other would be tantamount to closing one's mind to a certain type of answer, and to me that would be a failure.

A lot of people in the field feel that the signal is false, and that we will rule out LSND-type oscillations, with almost religious conviction. It belies their bias in what should be an objective pursuit. I think part of it stems from the saga of the 17 keV neutrino. In that case the scientific method was vindicated (although I am sure that there was plenty of subjective chatter amongst the participants, especially at conferences) but I think the experience left a lot of people in the field uncomfortable with new and different experimental results in neutrino physics. We will shortly learn whether or not the LSND result was a false alarm, or whether Nature is a lot more complex than we thought.

And I can't wait to know the answer, whatever it might be!

Posted on

Sunday, February 11, 2007

1 comments (Read/Add)

![]()

Labels: blind analysis, miniboone, neutrinos

08 February 2007

Cold White Matter, Cold Dark Matter

Post by Yoshi Today, London had its heaviest snowfall in years and years, though by the time I walked across Kensington Gardens, it was more slush than snow. Still, it was very pretty!

Today, London had its heaviest snowfall in years and years, though by the time I walked across Kensington Gardens, it was more slush than snow. Still, it was very pretty!

Prof Tim Sumner came downstairs from the Astrophysics group to give a seminar about the ZEPLIN III experiment, which was built on the 10th floor here, and recently transported to the Boulby Mine in Yorkshire.

It is a liquid and gaseous Xenon detector read out with photomultiplier tubes, and uses the ratio of two light signals, from scintillation and ionisation in liquid Xenon, to look for events with a signature that is characteristic of WIMPs (weakly interacting massive particles), a candidate for dark matter. It will soon start taking data, and will be probing the regions where Supersymmetric theories start predicting the existence of dark matter.

Personally, it was interesting to see the design and construction choices for their detector, having previously been in the group at Stanford building EXO, a liquid Xenon experiment looking for double beta-decay. The physics is completely different, galactic dark matter versus the nature of neutrino mass, but many of the challenges are quite similar.

Imperial Experimental Astrophysics Page

Posted on

Thursday, February 08, 2007

1 comments (Read/Add)

![]()

Labels: cold dark matter, physics seminar, snow in London

07 February 2007

Paint O'Clock!

Post by Jamie

Posted on

Wednesday, February 07, 2007

5

comments (Read/Add)

![]()